Indiana Conservation District Tackles Urban Problemsby Bob Oertel |

Lake County, Indiana, is a land of wide conservation contrasts. It stretches northward from farmlands in the south through mixed residential and business areas to the bustling commercial and industrial canyons along Lake Michigan. Change is constant as land shifts from once predominately agriculture to housing, commercial and other urban uses. Roof tops, streets and parking lots pave over the once open earth, hobbling its ability to absorb rainfall. Land disturbing activities of all kinds, whether for agriculture, urban, industrial or commercial development expose the earth to possible damaging soil erosion. The result, in too many cases, is sedimentation in sewers, creeks, rivers and eventually Lake Michigan and the other Great Lakes. All of the land that drains water into the Great Lakes is a giant interrelated ecosystem. Forty million people depend on the Great Lakes Basin for drinking water. Fifteen percent of the U.S. population and sixty percent of the Canadian population live, work and recreate in the basin. Thus, any erosion, and the resulting sedimentation, adversely effects water quality and the lives of people throughout the basin.

Conservation Districts Meeting the Challenge The Lake County Soil and Water Conservation District (SWCD), organized in 1944, is one of 207 SWCD's in the Great Lakes Basin. Each of these SWCD's has, over the years, been tackling the land and water problems within their respective district boundaries. Through cooperative working agreements with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Natural Resource Conservation Service provides technical services to districts in the U.S. Controlling erosion and water management on agricultural land was the first priority of work during the early years of the Lake County SWCD. But, in the early 1970's, the district and NRCS expanded their programs. Helping solve urban land and water use problems became a high priority as more and more land shifted from growing food and fiber to non-agricultural uses. Today, there are new partners in this expanding effort. Government agencies at all levels are working with rural and urban landowners to control erosion and sedimentation and protect the Great Lakes Basin's invaluable natural resources. Roger Nanney, NRCS District Conservationist, working with the Lake County SWCD, Crown Point, Indiana, is now stationed in the Chicago office of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency as liasion to the Great Lakes National Program Office. He deals with nonpoint source pollution from both urban and agricultural land. Through partnerships [with EPA, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Indiana Departments of Natural Resources (IDNR) and Environmental Management (IDEM), local communities and the NRCS], the Lake County SWCD has received grants to develop NPS pollution targeting plans and computer models to demonstrate Best Mangement Practices (BMPs). "The goal of the SWCD," says Phyllis Reeder, Administrative Assistant of the District, "is to plan, design, model and install highly visible, low cost BMPs that use existing technology to solve conservation problems in the Grand Calment River Basin." This basin was one of the 43 Areas of Concern (AOC) identified in the Great Lakes Basin by the International Joint Commission. The waters of the AOCs are highly polluted and considered toxic "hot spots". The Great Lakes Basin Program for Soil Erosion and Sediment Control, established in 1990, is a federal/state program with the specific goal of protecting and improving Great Lakes water quality by controlling erosion and sedimentation. The Great Lakes Basin Program also wants to limit nutrients and toxic contaminants and minimize offsite damages to harbors, streams, fish and wildlife habitat, recreational facilities and the basin's system of public works. BMPs Adapt Existing Technology Several Best Management Practices were established to correct soil erosion and sedimentation problems in the urban areas. "What we do," explains Roger Nanney, "is to adapt and use practices we have long used in our conservation work on farm land. Soil is the same no matter if it's in town or in the country. What works to control erosion in one place, we try to use in other places."

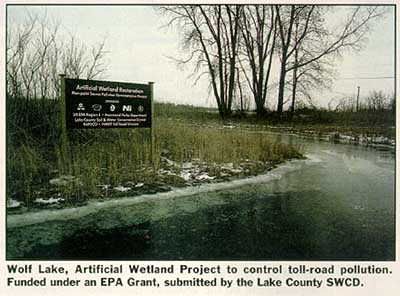

Toll Road and Wolf Lake Runoff from 20 acres of land, that included a toll booth area on I-90, drained down a 250 foot long ditch and emptied into Wolf Lake. Oil, grease, trash, salt and soil were being carried into the lake, ruining it for recreational use. This problem was solved by establishing a one-acre wetland between the drainage area and the lake to strain out pollutants. "We have used man-made wetlands to solve similar problems, so this solution looked logical to us," recalls Nanney. A shallow, level-bottomed pond was dug, leaving a peninsula in the middle. Trees were saved wherever possible to provide shade and hold down water temperatures. Banks of the pond were smoothed and seeded to a mixture of native plants, including both Little and Big Bluestem and other grasses. Straw mulch was spread over the seeded banks. On Earth Day, Boy and Girl Scouts planted cattails in the pond. The one acre wetland is designed to trap the first one half inch of runoff from the 20 acre watershed. "Most of the trash, oil and soil that will wash off will be in the first half inch flush of runoff," explains Nanney. At the request of the Hammond Park Department, 2,000 feet of eroding shoreline at Wolf Lake was treated by applying rock riprap. A grant from EPA, under their Clean Lakes Program went to the Lake Co. SWCD to fund the work. NRCS provided the technical assistance. The shore stabilization work protected clusters of Potentilla Silverweed, an Indiana endangered plant species found at the work site. Sand Filters at Marquette Park Lagoon Adapting a small self contained pollution control device used in East Texas, NRCS constructed two sand filters to clean up runoff from a 3 acre parking lot in Gary, Indiana. Runoff that previously drained into a catch basin carrying with it oil, grease and debris, instead now runs through two septic tanks. Each tank is divided in half. Entering the top of the first half of the tank, trash and sediment settle to the bottom while the water goes over a baffle into the second half of the tank. There the water soaks progressively downward through layers of gravel, filter fabric, sand and finally another filter fabric before being released through an outlet pipe to a lagoon. Tops of the tanks are easily removed when necessary to clean out accumulated debris. Dune Restoration at Gary Public Beach Each spring the city of Gary, Indiana has spent six weeks removing wind blown sand from the parking lot and road with front end loaders and leaf blowers. The sand was returned to the Lake Michigan beach where, each year, severe wind erosion would again blow the sand back on the parking lot. "It was an exercise in futility," says Roger Nanney, "but we had a solution. Working with the city, we restored a portion of the original dune and protected it to keep the sand in place." Once the dune was reconstructed in 1995, it was covered with a bio-degradable fiber blanket and pinned down with wooden stakes. The base was stabilized with rows of riprap. Neighbors and other volunteers then planted 60,000 plugs of beachgrass on one foot centers and top dressed the plants with fertilizer. "We learned the hard way," admits Nanney, "that planting in the summer isn't too successful. We had much better luck with fall plantings." So far, plantings on the lake side are doing better than those on the land side where sand is blowing on the plants. "We still hope some of these covered plants will recover," Nanney says. National Recognition for Lake County SWCD The district was given a vital role as a partner with the Indiana Dept of Environmental Management (IDEM) in carrying out Indiana's "Rule 5". The purpose of this bill, passed by the Indiana legislature, is "to reduce pollutants, principally sediment resulting from soil erosion from surface stormwater coming from construction sites." Any individual or organization disturbing five acres or more of land (farm land is excluded) must submit an application to the Indiana Office of Water Management, Permits Section, IDEM. The applicants must prepare a soil erosion control plan, meeting requirements described in the Indiana Handbook for Erosion Control in Developing Areas. The SWCD reviews the plan for technical adequacy and makes recommendations for changes if deemed necessary. This activity, plus the continuing technical assistance to farmers and the urban community and the Areas of Concern in the Great Lakes Basin have made the Lake County SWCD a vital conservation force. One of the highest recognitions for the widespread work of the Lake County SWCD came when it was named the Goodyear "District of the Year for Indiana" in 1996. Jack Nelson, a supervisor of the district governing body, joined supervisors from other districts in the U.S. early in 1997 as guests of the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Corporation in Arizona. "The people of this country look to the SWCD and the NRCS for help with all kinds of land use problems," says Roger Nanney, a 20 year veteran in conservation work. "But," he continues, "we consider what most folks say are problems as actually being opportunities - opportunities to improve our living environment and conserve our bountiful natural resources. L&W For more information, contact Roger Nanney, EPA - Great Lakes National Program Office or Phyllis Reeder, Lake County SWCD, 928 South Court Street, Suite C, Crown Point, IN 46307-4848, (219)663-0238, fax (219)663-2547. |

©2000, 1999, 1998 Land and Water, Inc.