Organic Soil Amendments for Enhanced Vegetative Coverby Sherri L. Dunlap |

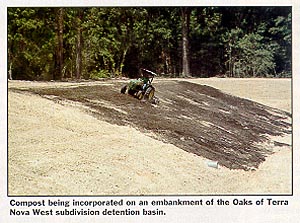

Introduction Organic amendments, such as compost, can help establish live, fertile soils in areas where sterile, impoverished soils exist. Organic amendments increase fertility, increase permeability and porosity, buffer pH, improve nutrient and moisture retention, increase cation exchange capacity, etc. We attempt to grow vegetation on disturbed urban soils and subsoils of Harris County, Texas; however, these soils have little resemblance to topsoils. The Harris County Flood Control District (HCFCD) is charged with soil reclamation of inhospitable soils in order to establish vegetation for erosion abatement on our earthen drainage channels. On two sites with very different soils, two different "mature" composts were added to overcome soil deficiencies. The Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission defines "mature compost" as the highly stabilized and sanitized product of composting which is beneficial to plant growth and has a reduction of organic matter (ROM) of 40-60%. Mature compost is dark brown to black and has a pleasant earthy smell. Mature compost has a soil-like appearance and, with the exception of partially decomposed wood fragments, none of the original feedstocks can be identified. The goal in adding soil amendments is to ensure shallow slope stability by producing adequate, self-sustaining vegetative cover. The first demonstration site is a detention pond constructed by the developers of The Oaks of Terra Nova West subdivision. The second demonstration site is on the Gulf Bank Detention Basin on White Oak Bayou. Oaks of Terra Nova West Detention Basin The topsoil in the detention area site at The Oaks of Terra Nova West is an impoverished, silty sand; it is highly erodible and represents a great many of the soils found on drainage channels throughout Harris County. Often, these soils can support the establishment of vegetation with the help of fertilizer; however, sustaining vigorous vegetation is difficult and the vegetation declines in vigor and growth as nutrients are extracted from the soil. The lack of soil particle cohesion (low clay and organic matter content) and vegetation leads to soil erosion. To improve soil properties, Living Earth Technology provided 60 cubic yards of composted greenwastes to be incorporated into the northeast corner (300 feet long by 30 feet high or 0.21 acres) of the detention basin embankment. We chose to incorporate 2-3 inches of soil amendment because we wanted significant soil structure changes, we wanted the organic soil amendment to supply nutrients, we wanted the beneficial effect of the amendment to be sufficient to establish self-sustaining plant and soil communities, and we wanted enough organic matter to last more than one season. Local high temperatures and high moisture levels cause very rapid decomposition and assimilation of organic matter. Ordinarily, compost amendment recommendations from university agronomists vary from 2-10 dry tons per acre; however, these recommendations are for farmers who annually incorporate compost. We added approximately 80-120 dry tons per acre. We may have gone a little overboard, but we wanted to achieve approximately 1-2% plant available organic carbon. We don't anticipate adding organic amendments again. In August 1994, the compost was spread on the northeast side of the basin to a depth of about 2 inches using a box blade pulled behind a tractor. The contractor attempted to incorporate the compost into the bone dry in-situ soils using a disk harrow; however, multiple passes were unsuccessful at mixing the two materials sufficiently. All areas of the site were then prepared per the HCFCD Turf Establishment Specifications; a temporary irrigation system was installed to provide water to the entire site. Post-installation inspections revealed a very low percentage of seed germination in the area containing compost; germination was normal outside the compost area. Observations in late October 1994, after a very heavy rainfall, revealed no soil erosion in the area containing compost, acceptable Bermudagrass germination in the few areas where the compost was mixed well with the underlying soil, and long (4+ feet) Bermudagrass stolons growing from adjacent areas into the compost areas. In some areas, the compost appeared to have traveled down slope as a result of the heavy rainfall; but, the soil surface was protected from erosion by the compost. I'm unsure why the Bermudagrass seeds did not germinate well in the composted material, maybe it was too "hot" - contained too much nitrogen - because it was not fully mature. Time may have allowed the compost to become more stable enabling the amended soil to support plant growth. We trusted the compost supplier's excellent reputation and did not submit compost samples for analysis prior to incorporation. The variable composition of feedstocks, temperature, moisture, compost management techniques (frequency of turning), etc. can impact compost stability. Analysis of the compost to determine ROM, Carbon:Nitrogen ratio, and salinity may have identified the problem(s) before incorporation. The amended area eventually produced a beautiful stand of Bermudagrass. This stand of grass easily withstood the prolonged drought of 1996-97. By the Spring of 1997, vegetation was seen only on the basin area where the compost was incorporated. Deep rills and gullies have formed in the remaining areas of the detention basin not amended.

HCFCD Gulf Bank Detention Basin The second demonstration site is a short slope on the HCFCD's Gulf Bank Detention Basin on the eastern edge of the basin. This repair area is approximately 180 feet long and 50 feet high (0.21 acres) on a 4:1 slope. This area was heavily rilled with sparse vegetation on a low fertility calcareous, clayey soil. Large quantities of 0.25 inch calcareous nodules littered the soil surface. In the summer, this soil bakes to the consistency of a brick; when wet, it is very plastic. The soil pH is also high (>8.6). These calcareous outcroppings are common on HCFCD drainage channel embankments and make it difficult to establish and sustain vegetation; they erode heavily as a consequence of sparse vegetative cover. CDR, Inc. provided 86 cubic yards of recycled waste product - co-composted lime stabilized bio-solids and land-clearing green wastes to incorporate into the in-situ soils. The compost consisted of one part lime stabilized biosolids and two parts green wastes compost. On acidic soils, the high pH of the treated biosolids will buffer the pH to a more beneficial (higher) pH. Using knowledge gained from work on the first demonstration site, in mid-November 1994, a chisel plow was used to break up the in-situ soil to a depth of 4-6 inches. Care was taken to insure an even 3 inch deep application of compost over the entire area. A rotary tiller, set at depth of 5+ inches, made multiple passes over the repair area to ensure intimate mixing of underlying soil and compost. It was obvious that mixing was occurring - the underlying soil is very light in color and mixing caused a significant change in the soil's color. This amount of soil amendment produced a soil with over 3% organic matter. Next, the surface was hydroseeded with Bermudagrass, crimson clover, fescue, and ryegrass to ensure good winter vegetation. While Bermudagrass is a warm season grass, our winters are frequently warm enough for germination of the desired permanent vegetation - Bermudagrass. Approximately one week after incorporation of the amendment, a 5 inch rain fell on this site. Despite the heavy precipitation no rilling was observed . By the third week, the site was covered in sprouting grasses and clover. Two months after planting, the vegetation was observed to be well established. Unlike other channel sites that experience a plethora of weed seed germination when the in-situ soil is distributed, the noxious weed - Johnsongrass - is no longer evident in the area of amended soil. While many pioneer plant species are well adapted to low fertility soils, an increase in fertility often allows different plant species to thrive. Soil structure has been so improved that you can grab a soil sample with your bare hands - no tools needed. Conclusion Compost's ability to create a living, self-sustaining plant and soil community capable of protecting the soil makes it a wise choice to help lengthen the useful life of our earthen infrastructure. At $12/cu.yd. F.O.B. ($0.11/sq.ft. at 3 inches depth) these organic soil amendments are expensive; however, compared to the usual accelerated repair frequency, it is a bargain. Typically, an organic soil amendment is less than 10% of a project's installed costs. If, in fragile highly erodible soils, an organic soil amendment lengthens the channel's useful life by only one year, it has paid for itself. Experimental work is being sponsored by HCFCD with the Texas Agricultural Extension Service ( a part of the Texas A & M University System) to determine the minimum quantity and quality of organic amendment (consequently the minimum expenditure) to produce the desired long-term vegetation quality. For more information, contact Sherri L. Dunlap, D. Eng., Biotechnical Engineering Manager, Harris County Flood Control District, 9900 NW Freeway, Houston, TX 77092, (713) 684-4000, fax (713)684-4140. |

©2000, 1999, 1998 Land and Water, Inc.