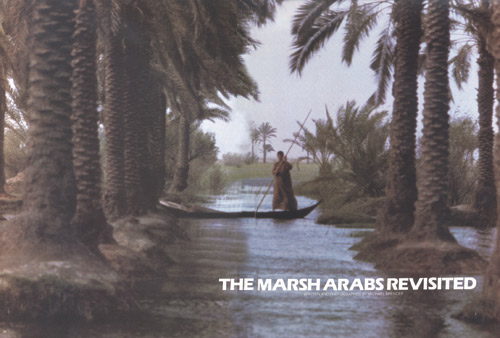

Restoring the Mesopotamian Marshlands in Southern Iraqby Sam Ali |

|

When I was just a small boy, my father would take me on canoe rides through the Mesopotamian Marshlands of southern Iraq. As we paddled slowly along winding narrow canals bordered by lush 15-foot-high reeds, I remember encountering a surprise around every bend: nesting ducks, a jumping fish, a herd of buffalos, a little reed hut with a boy fishing out in front. It was an amazing experience that I never forgot. I was observing first hand the Madaan, the "Marsh Arabs," whose protected way of life had changed little in 5,000 years. They lived then as they lived up until the late 1980s, in villages of reed huts sprinkled throughout the marshes, which they navigated in long carved canoes. The Madaan survived by spear fishing in the clear clean lakes of the marsh, raising buffalo, farming rice or harvesting dates for food and trade. And now the entire 6,000-square-mile marshland is almost entirely dried up. A 5,000-year ecosystem of birds, fish, buffaloes, vegetation and the indigenous human population is disappearing at an alarming rate, thanks to Saddam Hussein. But it all may come back. A year ago my firm, Psomas, began working with the Iraq Foundation to study ways to restore the Mesopotamian Marshlands of my homeland - a land I have not seen since I left for the U.S. in 1979 as a teenager.

Cradle of Civilization The balanced ecosystem of the marshland supported a broad diversity of life: vegetation, birds, fish, mammals, and humans. It served as a critical stopping point for birds migrating from Russia to southern Africa as well as a spawning area for fish in the Persian Gulf.

Environmental and Human Disaster The area became a refuge for Shiite rebel groups who hid in the marshes after the failure of the post-war uprising against Hussein. To flush out the rebels, Hussein launched an intensive round-the-clock effort to dry up the marshes. Hussein's engineers worked 24 hours a day for six months to build the 350 mile-long Saddam River to divert water from the Euphrates. He then ordered the Iraqi Government Drainage Project, a series of canals with telling names like Mother of All Battles Canal and Loyalty to the Leader Canal, to divert water from the marsh. In just a few years, the marshland shrunk from 6,000 square miles to just 500 square miles. According to a United Nations report, there is virtually no water left. United Nations researcher Hassan Partow says "It's absolutely phenomenal to see the destruction of an ecosystem of that scale in just five to six years." The draining of the marshland is having a global impact on climate and bird migration, endangering species of birds, fish, and mammals; impacting fishing at the Persian Gulf; and threatening the loss of valuable seed bank. And the indigenous population may be lost. The Marsh Arabs living in the swamps were also suspected rebels, and Saddam forced them out. Their water was poisoned, they were bombed, rounded up by troops, killed, or forced to march out of the wetlands. Some 70,000 fled to refugee camps at the Iranian border. The original Madaan population, which numbered close to 450,000 as recently as the 1980s, now numbers less than 40,000.

Marshlands restoration

Another analysis was performed based on the assumption of directing the water from the last remaining marshes, Al-Hawizeh, south to the dry Central Marshes. It is hoped that the seed bank still exists under the soil where the marshes were drained and that reintroducing water will rejuvenate the seeds and bring back the reeds. Since the land is very flat, there is no concern about erosion. Sediment transported and deposited in this area is typically good news. It will keep the land fertile along the sides of rivers and marshes for agriculture use.

Up until the end of the short Iraq war, the Eden Again team had no direct access to the marshlands. We were working by "remote access," relying on satellite pictures and reports. Most of the relevant documents were classified secure documents that the Iraqi government refused to make available. With the war ended and the Hussein government toppled, our team now has access to the documents we need and can get into Iraq to get a first-hand look at the damage to the marshlands. A planned pilot project will provide detailed topographic mapping, GIS analysis and hydrologic studies to use as the first step in a full-scale restoration effort. In addition to the considerable challenge of restoring the marshlands, there is the challenge of rebuilding the Marsh Arab culture. The know-how that survived for 5,000 years to build reed huts and catch fish in the marshes can disappear in just one generation.

There is hope - the signs we have seen so far on the ground are encouraging. Hussein opened up the dams just prior to the recent war in order to flood large areas and create problems for advancing U.S. troops. The tactic didn't work. But it brought hope for the Marsh Arabs. The timing was perfect, early spring, when the water level is high in the rivers and the temperature suitable for growth. The reeds began to grow once again, and the Madaan began fishing, building their canoes and huts on the water, and even exporting some of the reeds to Kuwait for use in fans and mats. If the Eden Again team has its way, this local initiative could be just a preview of the return of the Mesopotamian Marshlands to their previous splendor. For more information, visit www.psomas.com. About the author: Sam Ali is a civil engineer and water resources expert in the Costa Mesa, California office of Psomas, an engineering, survey and information management firm providing services to the public and private sector in water, land development, transportation, and information technology. Headquartered in Southern California, the firm has offices throughout California and in Salt Lake City, Utah. |

©2003 - 1998 Land and Water, Inc.