Restoring the Sand Hill Lakesby Faith Eidse |

|||

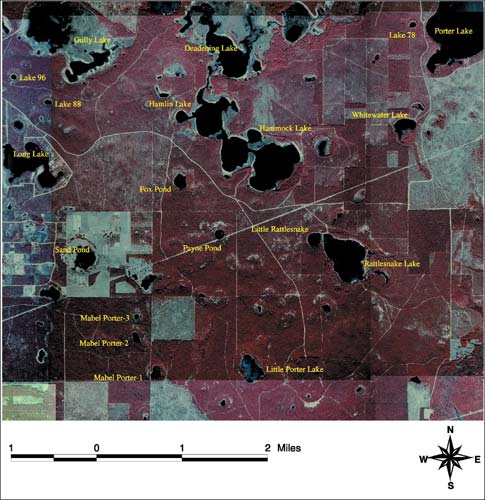

Aerial photograph of lakes in the project area. From the air the Sand Hill Lakes region north of Panama City, Florida, glints with more than 200 lakes, some small steep-walled, round-bottomed sinks, others larger flat-bottomed pools, including the popular Hammock and Hamlin lakes. There are so many lakes on this 50,000-acre karst terrain that some are unnamed. Instead they were numbered for this project, such as Lake 96, an example of a steep-walled sink lake. Rattlesnake Lake, also popular for recreation, has characteristics of both a steep-walled and a flat-bottomed lake, and also features a steephead stream flowing into it. Steepheads, so named by pioneers, are north Florida’s ever-flowing steep-walled ravines; moist regions of red and dusky salamanders. Usually formed from ancient barrier islands, seepage streams break through the foot of the formation, causing sand to slump into them and erode headward, from the bottom up, opposite a clay erosion gully, which erodes top down. A closer look at these lakes reveals that some of them connect directly to that portion of the porous limestone base that holds much of Florida’s water supply, the Floridan Aquifer. Overlain with soils and sediment, the aquifer releases water through pressurized channels into translucent springs that feed Econfina Creek, designated a Class I (drinking) water body. The creek in turn feeds Deer Point Lake Reservoir, the primary source of drinking water for Panama City, Panama City Beach and other municipalities in southern Bay County. “Recharge to the aquifer can be relatively rapid through some of the lakes,” said Paul Thorpe, during a recent assessment visit to restored sites. “In other lakes, however, deposition of clay and silt might actually impede seepage.” Thorpe managed a Northwest Florida Water Management District project in the Sand Hill Lakes to restore erosion sites and impacted riparian habitats and protect lakes and associated habitats from further adverse impacts. These actions, in turn, complement long-term land management strategies, including longleaf-wiregrass habitat restoration, public education and resource-based recreation. The District was awarded $300,000 in grant funds from the United States Environmental Protection Agency through the Section 319 Nonpoint Source Management Program, which is administered by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection Stormwater/Nonpoint Source Management Section. The project goal was to remediate sediment pollution from access roads cut down hillsides directly to various Sand Hill lakes, impacting sensitive riparian communities and leaving bare soil to wash into water bodies. Considerable study and analysis had convinced the District that it could most effectively protect water resources and drinking water supply through land purchases. It delineated the ground water recharge area for Econfina Creek and acquired 80 to 90 percent of the lands within the designated “Econfina Recharge Area.” In the largest single recharge area acquisition that District officials know of, they added nearly 29,000 acres in upland and Sand Hill Lakes recharge lands to significant stretches of Econfina Creek, and three springs in the Gainer springs group, the largest source of the Floridan discharge to Deer Point Lake. The total 40,898 acres in Washington, Bay and Jackson counties used $45.5 million of Florida Forever, Preservation 2000 and Save Our Rivers funds to protect the region known to provide two-thirds of the flow (300 million gallons per day) to Deer Point Lake Reservoir. “On a map you can see that this area features a concentration of lakes, which you don’t see anywhere else in this part of Florida,” Thorpe said. “Most of these lakes are closed basins, lacking direct surface water discharges. Scientists have further identified a particular plant community around the lakes, anchored by the state listed endangered and endemic smoothbark St. John’s wort (Hypericum lissophloeus) and associated plant species.”

The District started the restoration project in 1999, just as lake levels dropped during a historic three-year drought. Levels remained higher, however, in lakes fed by steephead seepage, such as Rattlesnake Lake, than in lakes with no inflow whose beds dried and cracked. Yet the smoothbark St. John’s wort, so named for its shiny chestnut brown stem casing, blossomed into yellow flowers, and produced multi-seeded capsules. “Smoothbark St. John’s wort was growing in near desert conditions during the drought and now they’re standing in water,” Thorpe said. As water levels rise, the plant forms woody, interlaced prop roots like those of the red mangrove. “This plant community has developed and adapted to these conditions only in this region,” Thorpe added. Local botanists, Dr. Edwin Keppner and Lisa Keppner, conducted a biological inventory of 96 lakes, sinkholes and basins in the Sand Hill Lakes and found that 76 have populations of the species, thus doubling the known number of sites for this rare plant. They warned, however, that residents who purchase lakeside property frequently remove the plant to provide a clear view and access to lakes and can destroy entire communities of St. John’s wort in this biodiversity hotspot, one of six so designated nationwide (by B.A. Stein et al. in Precious Heritage). During our evaluation visit, we turned north off State Road 20 and drove along Econfina Creek into the Sand Hill Lakes beyond. We turned west along Greenhead Road to reach Rattlesnake Lake. A sign permitted day use during the week and offered group camping by reservation only on weekends. Hunting and fishing licenses are required, as are Type I hunting permits from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. A fresh layer of limestone surfaced the road and, in ditches on either side, laborers had piled larger stones as check dams to slow stormwater runoff. We passed an old road to the lake that was growing into fresh forest and, descending on a new road that followed the terrain contour, approached an environmentally improved boat ramp. Water covered the boat ramp and lapped at new, heavy rail fencing that controlled driving and parking access and protected a vibrant community of slender Smoothbark St. John’s wort.

The hiking trail around the lake was covered in high water, so we looped back up the road and parked above the terraced hillside that had once been a gullied dirt road sending sediment into the lake bottom. “The Orange Hill Soil and Water Conservation District worked with us to address that,” Thorpe said, “by closing the road and creating a series of catchment basins going down the hill to stabilize that hillside and catch runoff. The terraced sites were then planted with ground cover and trees to help hold the slope in place and eventually merge with the forests around it.” The planting, however, occurred “during the height of the drought,” Thorpe added. “In some areas, the seedlings did not take well and had to be replanted….” On this visit, herbaceous plantings were well-rooted and holding soil effectively, preventing new erosion. “I think with any work like this,” Thorpe said, “you can’t just plant it and walk away; you have to go back and see whether, due to drought, or drought with subsequent rainfall, you might get some areas where erosion is restarted. It’s important to actively monitor restoration sites until they are well established.” Along the Little Rattlesnake Lake shoreline, plants grew green and vibrant. Above it another old road cut had been closed to traffic, terraced, planted, restored and was merging with existing forest. Yellow butterflies accompanied us up the terraced hillside. The view from the top was of a grassland growing back into longleaf forest, soon to merge with deeper forests on either side.

We descended again to the lake, scattering bees on yellow blossoms, and searching for a passage to complete our trek around the lake. The path we found was four feet high under overhanging pine boughs and would have made easier passage had we been deer. We reached the far shore and straightened up, noticing that a ridge between Rattlesnake Lake and Little Rattlesnake Lake, a former roadbed converted to longleaf habitat, was partially submerged. “It’s nice when nature can reward your efforts,” Thorpe said. “This was a road and now there are fish swimming in it.” The two lakes were now joined, with nature taking root between them. Ecological health seemed to be returning to the entire region. We drove to Fox Pond on a road that had been re-graded, its sides planted in green cover. A swale and catch basin had been installed and was tiled with latticed concrete to stabilize it and prevent further erosion. A berm was established between the lake and roadway, and longleaf pine, wiregrass and switchgrass were planted to control the energy of stormwater runoff. The lake, a reflecting mirror, was broken now and then by leaping fish. Bees, butterflies and dragonflies darted among green marsh grasses. “The District’s Division of Land Management and Acquisition had been thinking about roads and public usage for quite a while because they have come to know the area very well,” Thorpe said. Staff identified restoration sites with the help of District land management staff, a survey of protected species, analysis of digital aerial photography and field surveys of the project area. He ranked identified sites based on existing or potential impacts to aquatic and riparian habitats and listed species.

After closing access roads and restoring multiple areas, eroded gullies to Rattlesnake and Little Rattlesnake lakes, a canyon-like gully at Lake 96, an access road along a power line at Payne Pond, and erosion and sediment buildup on Mabel Porter Pond #1, funds were still available for additional work. Thus, the District was able to construct a swale and restore native vegetation at Fox Pond. At Hammock Lake a berm was built, vehicle exclusion fencing installed and a sedimentation basin was built. Gully erosion was stabilized at Little Steephead. Northeast Rattlesnake basin was also stabilized and restored with native vegetation. From January 2001 through May 2003, the District contracted with Orange Hill to complete these erosion control steps, restoring native vegetation to 12 sites in the project area and using various Best Management Practices. Soils were stabilized, the land was recontoured with earth moving equipment, and switchgrass was planted to provide stability during initial grow-in periods for longleaf pine and wiregrass. The effect of these restoration actions was to eliminate road footprints and reduce the number of unsuitable access roads to some of the lakes. The District also contracted with the Washington County Sheriff’s Department to enforce vehicle exclusion and to prohibit dumping. In addition, the District sampled surface water quality from five sites and found it to be good, except for the sediment deposits in lakes and shorelines, which the project was designed to address. Lake levels were monitored at Rattlesnake Lake and Lake 96, a significant measure since drought persisted during most of the project period and explained the need for replanting in some areas. Finally, plants were monitored using fixed transects and, despite drought, native Smoothbark St. John’s wort and threadleaf sundew flourished in formerly barren roadways at Rattlesnake Lake.

To implement an educational component, the District revised and reprinted 3,000 workbooks from its Waterways environmental education program and distributed a portion to public middle schools in Washington and Bay counties. Through the Surface Water Improvement and Management (SWIM) program, the District also developed a foldout map-based educational brochure focusing on the St. Andrew Bay watershed, including the Sand Hill Lakes. Most of the 7,000 brochures have been distributed through school programs and environmental events. Thorpe, who coordinated contract management and vegetation transect and water quality monitoring, summed up, “The restoration and the erosion control were contracted out as a series of tasks to be performed by the Orange Hill Soil and Water Conservation District. We did some cost comparison with private sector companies, and they compared favorably. Staff from USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service provided a great deal of technical assistance throughout the project. Orange Hill worked with Washington County to complete the onsite work.” Before leaving, we hiked down through longleaf pine seedlings and yellow blossoms to sapphire Lake 96. Its canyon-gullied road had become impassable and was being used as a refuse dump before restoration. “There’s some inherent conflict with different types of goals and user groups,” Thorpe said. “You have people who want to hunt, people who want to ride horses, people who want to hike and people who want to fish and picnic, and we try to facilitate all user groups by creating separate trail opportunities for each.” For example, volunteers of the Florida Trail Association have extended a nearly 14-mile segment through the District’s Sand Hill Lakes property. But protecting the water resources and habitat still come first. For further information contact Paul.Thorpe@nwfwmd.state.fl.us or 850-539-5999 ext. 128, The Northwest Florida Water Management District, 81 Water Management Dr., Havana, FL 32333. |

©2003 - 1998 Land and Water, Inc.