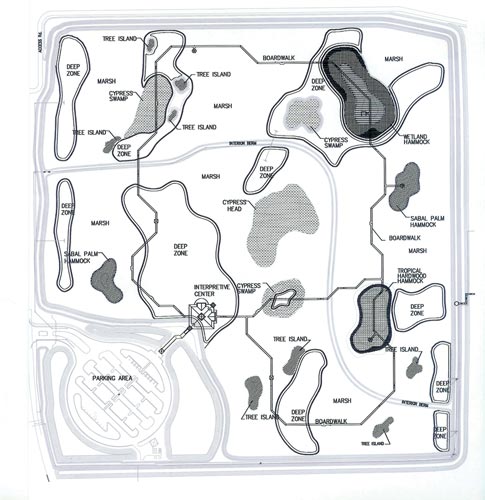

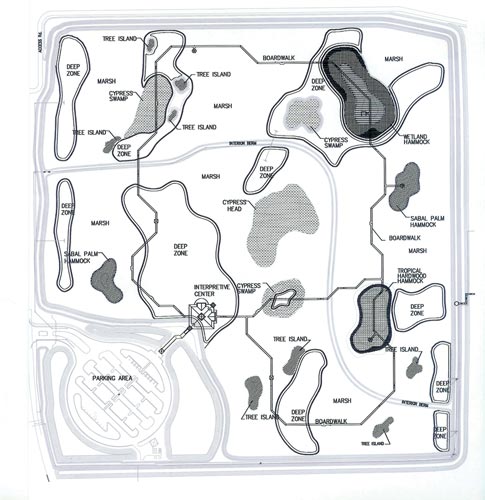

Green Cay Wetland Site Plan

Background

Florida is the fourth most populous state in the nation and is expected to continue growing from 14.2 million residents in 1995 to about 20.7 million in 2020. Palm Beach County, situated on the southeast coast of the peninsula, has absorbed a high proportion of the added population with a concurrent rise in the demand for drinking water and wastewater treatment. In a progressive environmental effort, the Palm Beach County Water Utilities Department constructed Wakodahatchee Wetlands, a 50 acre wetland, to operate in conjunction with a nearby wastewater treatment plant, using the wetland system to filter the nutrient rich water. Much of the “treated” water is then reintroduced into the water cycle through percolation and evapotranspiration. Public access via a raised boardwalk creates an opportunity to educate the public while the wetlands provide water quality improvement as water is processed through the wetland cells. A diversity of over 150 species of native and migratory birds, including Green Heron, Osprey, Woodstork, Anhinga, Purple Gallinule, Black-necked Stilt, Palm Warbler and Belted Kingfisher use the wetland habitat. Marsh rabbits and a transient Bobcat have inhabited the associated upland.

The Project

Palm Beach County was fortunate to have the rare opportunity of expanding their operation by purchasing a 170 acre parcel across the street from the existing Wakodahatchee Wetlands. During this time, the last remaining local farms and tracts west of the coastal cities were being sold at great profit to land developers. Long time residents, farmers and environmental proponents Ted and Trudy Winsberg, agreed to sell their farm at a greatly reduced price with the condition it would be used to create additional treatment wetlands and habitat. Hazen and Sawyer, P.E., consulting engineers to the Palm Beach County Water Utilities Department (PBCWUD) contracted Restoration Partners, Inc. (RPI) to design the new, treatment wetland. Building on the lessons learned from the existing 50 acre wetland, RPI assembled a diverse team of wetland experts to consult to the PBCWUD staff and designed a master plan incorporating both water treatment and public education. The resulting design included a variety of wetland habitats, with water flow directed through shallow and deep zones to maximize treatment, and transitional zones to accommodate water fluctuations.

Design Criteria

Three main design goals drove the team’s decisions throughout the project: 1)Wastewater Treatment , 2) Habitat Creation and 3) Public Education. Water treatment was needed to accomplish filtering of the secondary effluent entering the wetland to meet or exceed ground-water quality standards. The existing Wakodahachee Wetlands offered insight into a successfully operating treatment wetland in a similar set of conditions. Both existing and newly designed wetlands require processing the same secondary effluent to the same standards. Although treatment of the water at Wakodahatchee has been successful, the team was challenged to build and improve upon its design concepts.

Habitat Creation and Public Education were equally important design goals. With a high emphasis placed on public access and environmental education, RPI chose to weave site interpretation needs into the overall wetland and site planning from concept to final design. This provided the opportunity to design the wetlands with the framework for optimizing educational opportunities and public access.

A hand-built Native American Seminole Chickee like the one pictured will be used as a pavilion on the Wetland Hammock Island.

The Water Treatment System

At Wakodahatchee, treated wastewater (secondary effluent) enters the system as influent into six cells, flows over shallow and deep planting zones, moves to a collector canal via control structures, and then enters a final pond for polishing. During this treatment train through the wetland cells, a host of processes take place to reduce, immobilize or break down compounds and reduce pollutant loadings. The average residence time for the entire cycle is approximately 16 days. Movement between the cells is controlled from the treatment plant by mechanized control structures. This can be manipulated to suit conditions: for instance, for an approaching hurricane the PBCWUD can draw the water down for more stormwater storage capacity. They can also retain the wastewater longer for more treatment time. The evapo-transpiration level is so high that the Department can recycle the remaining water back through the system rather than send it to deep well injection. A nearby golf course uses reclaimed water for irrigation. This reclaimed water is nearly drinking water quality, with phosphorus, nitrate-nitrogen, fecal coliform, BOD and COD reduced to below Florida Department of Environmental Protection allowable levels for Class III waters. Nitrate has a hundred-fold reduction through one cycle. Ironically, the biggest polluter in this system is the wildlife. Coots and moorhens, in particular, descend on this system in great numbers, and their fecal contribution constitutes a notable and measurable pollutant loading. However, it is a “problem” the PBCWUD has decided to live with, because the spectacular wildlife that people come from all over to see helps make this project such a success.

The layout RPI developed for Green Cay is comprised of two large cells as opposed to 6 cells at Wakodahatchee. This will result in longer residence time for the water entering the wetlands, reducing the need to re-pump water back through the system, less stress on the wetland system, greater wetland treatment area (resulting from reduced berm:wetland ratio) and larger expanses of shallow sheet flow. The basis of the design is to create a long flow path of the influent through the system, keeping the flow on track by intercepting “short-circuited” flows with deep zones to return the water to a sheet flow pattern. One of many challenges was to provide maximum plant surface contact. The most successful plant species at both water treatment and long-term survivability present at Wakodahatchee were used in higher percentages at Green Cay although not exclusively in order to maintain high plant diversity.

Green Cay lies within the Everglades Ecosystem, a system so unique as to have global designation. The alligator, a keystone species of the everglades, will no doubt take up residence in the cypress swamps of Green Cay.

Plant Selection and Creating Habitat

The Everglades ecosystem was used as a template for the overall site plan, mimicking the open expanse of sawgrass/marsh habitat with intermittent tree islands and cypress heads. When looking at the world biosphere that is the Everglades, the RPI team wanted to represent as many native plant communities as possible, in effect, creating a showcase of south Florida wetland habitats to create a diverse teaching palette. The selected habitats included Open Water, Shallow and Deep Freshwater Marsh, Cypress Swamp, Tropical Hardwood Hammock, Wetland Hammock, Cabbage Palm Hammock and Wetland Tree Islands. Wetland/ upland transitional zones associated with these communities were included in the design and provide some of the most diverse habitat on site. Periodic draw-downs of water levels within the two wetland cells were prescribed to replicate seasonal water fluctuations in these natural environments, which many species require for long-term survivability. Canopy and understory species lists were developed for the forested communities to create a layered effect at time of installation. Maturity of canopy plant material ranged from tree-spaded 40’, 24’ and 16’ specimens to 9-12’ field grown. Many canopy species were also included in the understory at a 3-gallon size. Dead trees or “snags” were also specified for installation for their value in attracting certain wildlife species and will be strategically located on the fringes of islands and in the marsh. A comprehensive exotic removal and maintenance plan was written to keep the ever-present onslaught of exotic and pest plants under control.

Plant species selection was at the heart of the project. The design required plants that would be effective for water treatment, survive long hydroperiods, blend together in communities, support wildlife, and tell a story about the everglades and the water cycle. Project Manager, Dianne Lennon decided to start with consulting the expertise of two highly respected South Florida based botanists, George Gann with The Institute for Regional Conservation and Richard Moyroud. The team began by reviewing a master list of all known naturally occurring species of the south Florida wetlands habitats showcased in the project compiled by The Institute for Regional Conservation’s database. From this list plants were eliminated that would not be commercially available or were known not to withstand the site conditions. Emphasis was placed on a high level of diversity with 86 species of trees, shrubs, grasses, forbs, emergent and submergent aquatics selected. Each species was assigned a percentage of cover based on both what would naturally occur within the habitats and adjustments to take into account water treatment capabilities. This resulted in the highest level of diversity, the most accurate representation of the habitats and the hardiest species for the job.

Designing for Education and Community Involvement

Most residents of Florida consider the Everglades ecosystem to be remote and unrelated to their lives. It appears as a vast, mysterious water world of skin-slicing Sawgrass; populated by alligators, snakes and biting insects. Long-legged birds wade or gracefully glide through endless pure blue skies. The Everglades, making up a large portion of the state, are something to look at, but not touch. Through this lack of connection to the real Florida, residents and decision makers have created a web of environmental problems and challenges. Understanding wetlands, local hydrology and water conservation is a step in reversing the degradation.

Public access and a small interpretive program at Wakodahatchee have led to a strong connection with residents in the area. Those once opposed to the project, now embrace it. Through regular and repeat visits, a bond has been created between birds, plants, animals and people. To expand public environmental education efforts, Green Cay was chosen as the site for an interpretive center and boardwalk. The purpose of this facility will be to teach residents about water and human usage, wetlands and the value of creating habitat. This center will be one of four interpretive centers planned for Palm Beach County. The main themes of each center are interrelated, with the intent of leading visitors to experience all four to receive the complete story of local ecology.

To address the goal of public education, Restoration Partners included a site interpretation specialist on the wetland design team. The field of site interpretation delves into the experiences and perceptions a person has while visiting a site. It answers practical questions, such as how many visitors can be accommodated and in what size groups, where to locate drinking water, what information needs to be displayed, what protection from the weather is needed, and many other issues related to daily operations. Specific consideration is given to determining exactly what a visitor experiences and how it is experienced. This planning answers questions, such as “What distinct messages do we want to convey?”, “What should someone learn from their visit?” and “What new perceptions will be fostered?” The RPI team design will both help engage the public in the wetlands they are visiting and provide teaching opportunities for educators using the site.

The process started with identifying core educational messages, including understanding Florida wetland habitats, species, and many aspects of wetland ecology. A visitor profile was created. This was composed of residents, seasonal visitors, school groups, special interest groups, university level programming and conservation organizations. Finally, the visitor experience was mapped out and incorporated into the overall design.

Wakodahatchee has become a hot spot for bird watchers and photographers.

While designing habitats, the team gave consideration to the total visitor experience from point of entry at the interpretive center and continuing along the wetland boardwalk. Two options, the 1 1/2 mile full boardwalk loop and a shorter cut off route, will allow visitor’s time constraints, abilities, level of interest and other variables to be accommodated. Vistas typically found in the Everglades were created at key viewing points. Turns in the boardwalk as well as purposeful placement of mature trees were also used to frame views or slow down the pace to encourage closer examination of a habitat or highlighted species. Walking along the boardwalk, a visitor will experience the open expanse of marsh dotted with tree islands (critical nesting habitat for many bird species), explore the dense shaded interior of a tropical hardwood hammock and wind through a cypress swamp. Shade pavilions were located to allow visitors to linger or an educator to gather their group. Overlooks and seating were strategically positioned along the boardwalk to accommodate group tours.

Special additions to the design, such as a hand-built Seminole Chickee (local Native American traditional dwelling) and the inclusion of a deep-water “hole” within a cypress swamp, which would typically be used by certain species like alligators during the dry season, were included to provide points of interest. Interpretive signage and self-guided walks can now lead visitors to learn about individual ecological and cultural concepts. Also, the need for attracting wildlife to within watching view of the boardwalk while maintaining enough distance to not disrupt normal wildlife activity was considered while positioning islands and selecting plant species. The design will give great numbers of the population - people removed from the real Florida environment- the experience of Florida’s wetlands without getting wet!

Unique opportunities within urban landscapes

The Green Cay Wetlands will help filter valuable freshwater, while providing a regional destination for birders, nature photographers and residents to experience wetland ecology and water conservation first-hand.

Green Cay Wetlands is currently under construction and scheduled for completion in 2004.

For more information you may contact Dianne Lennon at www.restorationpartners.com.

References

- Mitsch, W. and Gosselink, J. Wetlands Third Edition, John Wiley and Sons, 2000.

- Kadlec, R. and Knight, R. Treatment Wetlands. Lewis Publishers, 1996.

- Schnoor, Jerald, D. Phytoremediation. GWRTAC, 1997.

- Personal conversations with James P. Ludwig Ph.D, Etoxicologist and Biochemist, Applied Ecological Services, Inc. January-February, 2004.

- Manahan, S. Fundamentals of Environmental Chemisty, Second Edition. Lewis Publishers, 2000.

Special thanks to Brian Winchester, Treatment Wetland Specialist for the team for his contributions to this article.

|